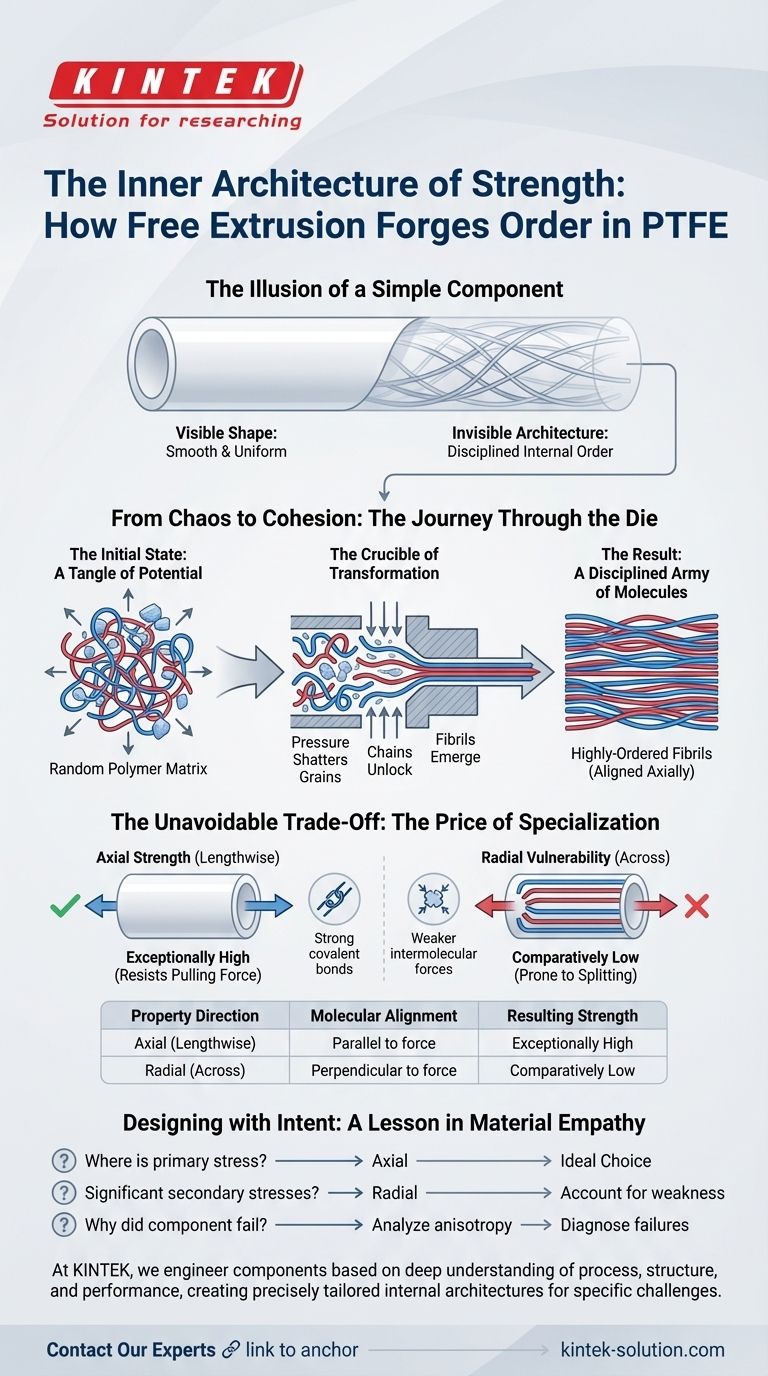

The Illusion of a Simple Component

A PTFE liner appears simple. It's a smooth, uniform tube. But this perception is a profound illusion.

Its true performance—its ability to withstand immense stress without failing—isn't determined by its visible shape. It’s determined by an invisible architecture, an internal order forged under extreme pressure.

Understanding this architecture is the key to engineering components that don't just fit, but function with intent.

From Chaos to Cohesion: The Journey Through the Die

The story of a high-strength PTFE liner is a story of transformation. It begins with a material in a state of random potential and ends with a structure of disciplined, focused strength.

The Initial State: A Tangle of Potential

Before extrusion, PTFE is a matrix of long-chain polymers. These chains are partially folded into dense crystal grains, but the overall orientation is random. Like a tangled ball of yarn, it has inherent strength, but no direction. Force applied to it will pull on the tangles, but not on a unified structure.

The Crucible of Transformation

As the PTFE is forced into the extrusion die, it enters a crucible. The intense pressure and shear forces are not merely shaping the material; they are fundamentally re-engineering it.

This energy shatters the tightly-packed crystal grains. It "unlocks" the folded polymer chains, freeing them from their random arrangement and making them available for a new purpose.

The Emergence of Fibrils

As the now-fluid material stretches, something remarkable happens. The individual molecular chains begin to align with the direction of flow. They pull taut, organizing into incredibly fine, thread-like structures called fibrils.

Imagine pulling a cotton ball apart. The initially random mass of fibers straightens out, aligning in the direction of the pull to form a stronger, more coherent strand. This is precisely what happens at a molecular level inside the die.

A Disciplined Army of Molecules

The result is a structure transformed. The once-chaotic matrix is now a highly-ordered assembly of fibrils, all pointing in the same axial direction—parallel to the liner's length.

When a pulling force is now applied along that axis, the load is borne by the powerful covalent bonds along the backbones of millions of aligned chains. The material is no longer a random network; it is a disciplined army, aligned to resist a specific threat.

The Unavoidable Trade-Off: The Price of Specialization

There is a universal law in engineering, as in life: you cannot be great at everything. Optimizing for one strength often requires a sacrifice elsewhere.

The free extrusion process makes PTFE anisotropic. It deliberately creates direction-dependent properties.

- Axial Strength: Along its length (the direction of extrusion), the liner becomes exceptionally strong and resistant to stretching.

- Radial Vulnerability: Across its diameter (perpendicular to the extrusion), it is comparatively weaker. A force trying to split the tube wall acts between the aligned fibrils, not along them, meeting far less resistance.

This isn't a flaw; it's a specialization. The process trades uniform, mediocre strength for exceptional, targeted strength.

| Property Direction | Molecular Alignment | Resulting Strength |

|---|---|---|

| Axial (Lengthwise) | Parallel to force | Exceptionally High |

| Radial (Across) | Perpendicular to force | Comparatively Low |

Designing with Intent: A Lesson in Material Empathy

This understanding changes how we approach design. It moves us from simply specifying a material to developing an empathy for it—knowing how it was made, where it excels, and where it is vulnerable.

When evaluating a component, the primary questions become:

- Where is the primary stress? If the dominant force is tension or pulling along the component's length, a free-extruded part is the ideal choice.

- Are there significant secondary stresses? If the application involves high radial pressure or splitting forces, this inherent weakness must be accounted for in the design specifications.

- Why did a component fail? Understanding anisotropy is often the key to diagnosing failures that otherwise seem inexplicable. The direction of the force is as important as its magnitude.

At KINTEK, we don't just fabricate PTFE components; we engineer them based on this deep understanding of the relationship between process, structure, and performance. Whether for semiconductor, medical, or industrial applications, we leverage processes like free extrusion to create liners, seals, and labware with a precisely tailored internal architecture.

We build for purpose, ensuring the invisible structure of your component is perfectly aligned with the challenges it will face. To ensure your components are engineered for their intended function, Contact Our Experts.

Visual Guide

Related Products

- Custom PTFE Parts Manufacturer for Teflon Parts and PTFE Tweezers

- Custom PTFE Parts Manufacturer for Teflon Containers and Components

- Customizable PTFE Rods for Advanced Industrial Applications

- Custom PTFE Teflon Balls for Advanced Industrial Applications

- Custom PTFE Sleeves and Hollow Rods for Advanced Applications

Related Articles

- How PTFE Solves Critical Industrial Challenges Through Material Superiority

- The Physics of Trust: Why PTFE Is the Bedrock of High-Stakes Electronics

- Why Your High-Performance PTFE Parts Fail—And Why It's Not the Material's Fault

- Your "Inert" PTFE Component Might Be the Real Source of System Failure

- The Physics of a Perfect Fit: How PTFE Eliminates an Athlete's Hidden Distractions